The City of Pittsburgh has its fair share of famous natives, but when it comes to well-known artists from the area, one name tends to ‘pop’ into people’s heads—and that is, of course, Andy Warhol.

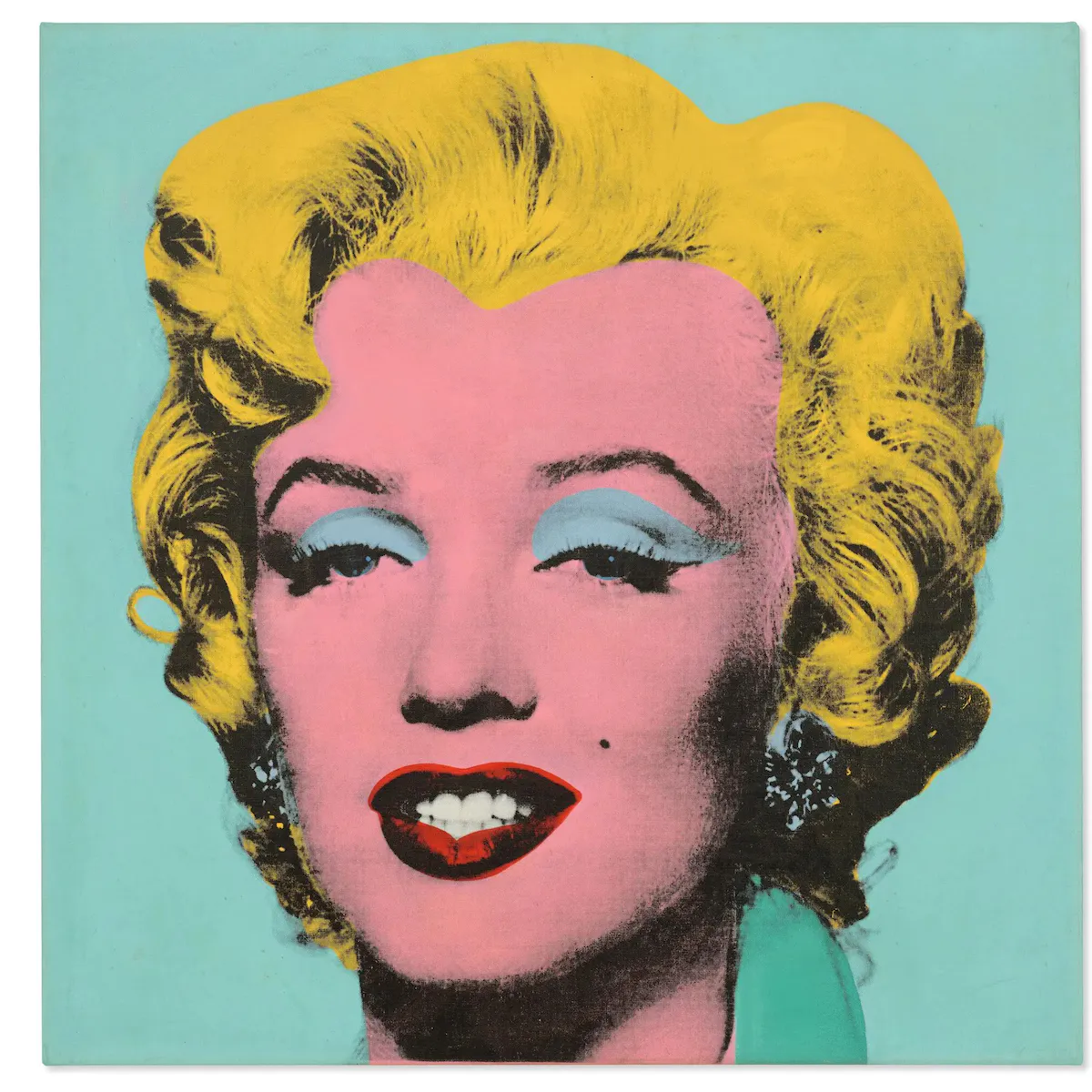

Born Andrew Warhola, Jr. on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Andy had a wildly successful art career in New York. From an early age, Warhol quickly carved out a path for himself in the commercial arts at Carnegie Mellon University, and eventually imprinted himself into the art world with his notable pop-art style silk screens of Campbell’s soup cans and other cultural icons, including Marilyn Monroe, Jackie Kennedy, Elizabeth Taylor, and most relevant recently, his works depicting the musician, Prince.

Following Warhol’s death on February 22, 1987, he returned to Pittsburgh for his final resting place at St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Cemetery. Much of Warhol’s artwork also returned to Pittsburgh, in the form of donations by the Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”), a New York non-profit organization committed to the advancement of the visual arts and the preservation of Andy Warhol’s legacy, to The Andy Warhol Museum (“Museum”), one of four Carnegie Museums located in Pittsburgh. The Museum is a shrine to the artist’s legacy, touting the largest collection in the world of his work, including silk screen prints, drawings, paintings, and films.

On October 12, 2022, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case filed by the AWF (not the Museum) against the accomplished photographer and creative entrepreneur, Lynn Goldsmith.

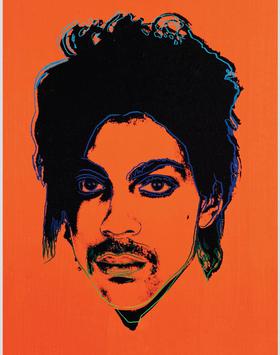

The controversy before the Court arises form photographs of Prince that Goldsmith took in 1981. In 1984, Goldsmith’s photographs were licensed to Vanity Fair magazine to use as an artist reference, who commissioned Warhol to create an image of Prince for publication alongside an article about the musician and credited Goldsmith with the “source photograph.” Warhol ultimately created fifteen silk screens of the Prince pieces, which became known as the Prince Series. Ownership of the Prince Series belongs to the AWF, which donated four of the silk-screen prints to the Museum. The AWF also licenses the Prince Series for commercial, editorial and other museum use.

Following Prince’s passing in 2016, the AWF once again licensed one of the Prince Series to Vanity Fair for publication in its Prince tribute issue. This time, Goldsmith received no credit as the source image. Therefore, Goldsmith notified the AWF of its alleged infringement of her copyrighted work, the AWF sued Goldsmith claiming that Warhol’s Prince Series was a “fair use” of her original photograph, while Goldsmith counter-sued the AWF for copyright infringement. After conflicting decisions from the federal district court in New York, which ruled in favor of the AWF, and the Second Circuit Court, which sided with Goldsmith, the case was brought before the Supreme Court to decide whether Warhol’s silk screen prints of Prince, infringed Goldsmith’s copyright by failing to satisfy the transformative use test under the law’s current fair use analysis. Stephanie Dangel, a Professor of Practice who currently teaches entertainment law at Pitt Law School, shared her impressions of the case. She noted, “Initially, when the Second Circuit decision came out, I think many Pittsburghers thought, ‘What does this mean for The Warhol Museum?’ because so much of his work is inspired by other artistic works and photographs.

Thankfully, Goldsmith did not challenge the original Prince Series of prints. Instead, she challenged the licensing rights related to those prints. However, the potential impact of the Supreme Court’s opinion on the work of Warhol and other appropriation artists is an open question.”

Prior to joining Pitt Law School, Professor Dangel was a law clerk for the late Supreme Justice Harry Blackmun and the former New York federal court judge, Judge Pierre Leval, who is famous for his “transformative” fair use test. Under Judge Leval’s test, an unauthorized use of copyrighted materials is more likely to be a “fair use” if it is “transformative,” or meaningfully different from the original work in terms of its message, meaning, function, or purpose.

Fair use, as Professor Dangel described, is an affirmative defense that in some circumstances allows for the unlicensed use of a copyrighted work. There are at least four factors codified in law that courts will consider in determining whether something meets the fair use threshold:

(1) purpose and character of the use, including whether the use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,

(2) nature of the copyrighted work,

(3) amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole, and

(4) effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Professor Dangel, who was also a filmmaker, learned first-hand from her filmmaking experiences that the AWF can be “very protective of Warhol’s works, and understandably so, since Warhol’s work is the forms the bulk of what they own.” In a documentary Professor Dangel produced about Pittsburgh, she said, “We talked about Andy Warhol and shot in The Warhol Museum. Even though we had permission to shoot in the Museum, and we interviewed the curator at the time, some of Warhol’s artwork was in the background. The Museum flagged the legal issue for us, saying, ‘We do not own all of the rights to this artwork. The Foundation owns some of these rights.’ In using the background images in the film, we ended up relying on a law firm’s fair use opinion and errors and omission insurance to protect ourselves, but I’m not sure that would have protected us from a lawsuit by the Foundation or the original photographer, if our film had been more successful.”

Professor Dangel also noted that the film included an interview with Andy Warhol’s nephew, who at the time worked in the Warhola family scrap business on Pittsburgh’s Northside. “The nephew was a good artist, including a tattoo he designed for himself based on his uncle’s Marilyn Monroe silk-screen print. But if the Supreme Court holds that the licensing of Andy’s work is not a “fair use” of Goldsmith’s photograph, could a photographer of Monroe or the Warhol Foundation sue Andy’s nephew over his Marylin tattoo? It seems ridiculous, but who knows?”

Given her filmmaking experience, Professor Dangel stated that now when she talks to her students about fair use, she emphasizes this an affirmative defense. She continued, “It’s a lot of money to litigate a copyright case, for those arguing in favor and against fair use. Lynn Goldsmith learned this the hard way, as her legal fees for the lower court cases were over $400,000. The Supreme Court case may have resulted in millions of dollars in legal fees, which led her to launch a GoFundMe campaign. Given these potential litigation expenses, I tell my students that, if you can afford to license the material, you should.”

Up until two years ago, the Supreme Court had not considered a similar fair use case since 1994—nearly 30 years ago—when it adopted Judge Leval’s transformative use test. Now there have been two fair use cases brought before the Supreme Court in the past two years. In April 2021, in Google v. Oracle, the Supreme Court ruled that Google’s use of source code owned by Oracle was protected by the fair use doctrine. However, the Google and Warhol cases may signal that changing technologies could require changes in the law.

Whether such changes in the law would benefit by from judges who are also trained in the arts remains to be seen. “Interestingly,” Professor Dangel pointed out, “[Judge Leval’s] wife, Susana Torruella Leval, served as curator and director of El Museo del Barrio throughout the 1990s. So, Judge Leval is very familiar with the art world. I believe that the transformative use test for him was quite a natural extension of both his legal opinions and his personal connection to the art world.” This insight led her to “wonder how Justices like Ginsburg and Scalia, who were very big fans of artistic works, particularly opera, might have tilted their decision on fair use in one way or another… whereas other Justices, who are not as familiar with the arts, might focus more on the commercial market for the works, rather than their transformative use. It will be interesting to see how much the personal backgrounds and interests of the Justices might play into how they approach this decision.”

Still, what makes this case so interesting to Professor Dangel and others in the legal and art communities is that there are artists on both sides of this case. The decision will “affect artists, both pro and con, depending on whether or not you’re the artist who created the ‘original’ work, or the artist who ‘appropriated’ the original work.” As Professor Dangel explained, “this will not be a pro- or anti-artist decision, because it depends on which artist you are representing.”

But for now, the art law world waits anxiously for the Supreme Court to speak on these issues. The Court’s opinion will likely be issued by July of this year. In the meantime, the oral argument is available here for further information and background on the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith case.

– GM